The Garden of Earthly DelightsIrish Arts Review (Dublin, Ireland)

By GERRY WALKER

When Hieronymous Bosch created his vision of The Garden of Earthly Delights c.1500, he sought to depict a world in resolute pursuit of sinful pleasures. The triptych charts the history of creation and the pervasiveness of sin. It is a cautionary tale in a surreal setting, calculated to induce an awareness of the drastic consequences of worldly indulgence and the urgent necessity for repentance -- a grand narrative whose tone is zealous and didactic both in intent and effect. Happily the current exhibition by Graphic Studio artists, also called The Garden of Earthly Delights, at the Chester Beatty Library, is a lot more life-affirmative and a lot less life-prescriptive.

Historically we are familiar with the idea of the garden as a metaphor. The physical will-to-form not only reflects our ability to subdue, shape and cultivate the natural world, it also demonstrates and enables the desire to contemplate a spiritual inner space. Hence Japanese and Chinese gardens are noted for restraint, Islamic gardens espouse symmetry and Christians attempted to celebrate romantically the Creation itself. In all instances, aside from physicality, the true spaces created were interior, contemplative and philosophical.

This is the context in which the Graphic Studio formulated a brief for its members and invited guests to each produce a limited edition print using traditional printmaking techniques in response to garden spaces and related imagery as they are represented throughout the collection of the Chester Beatty Library. Each participating artist was encouraged to use the collection as a resource and point of inspiration in the creation of their own Garden of Earthly Delights.

Initiated by the Graphic Studio, the show is a collaborative project with the Chester Beatty library. It follows on from another successful venture with the library the Holy Show in 2002 in which artists were invited to give a visual response to biblical texts using sources and references from part of the considerable print collection held in the library. A similar successful joint venture with the National Gallery entitled Art/Art in 1998 was based on responses to the gallery collection. In all cases there was a desire on the part of the Graphic Studio not only to initiate a dialogue between the old and the new and to unite a disparate group of artists behind a common theme, but also there was a recognition of the need to foster collaboration with other significant cultural institutions. The effects are, one feels, inevitably mutually beneficial. The dialogue between old and new, results in renewed interrogation of the value of national collections. It reinvigorates and reinforms the imperatives of curatorship itself and it creates a wholly new stream of work with the process of each engagement.

These collaborations are indicative of an inherent dynamism within both participating institutions. The Chester Beatty library has a substantial European print collection numbering . over 35,000 items. This is the largest collection of Old Master prints in Ireland. Chronologically the collection extends from the 15th century with early woodcuts to the 1960s and it includes some works from the Graphic Studio which Beatty purchased when he lived in Ireland. The library also has a policy of constantly evaluating and re-presenting its collection along with promoting greater accessibility in an innovative manner. This was evidenced recently in Irish writer Colm Toibin's curatorship of selected blue artefacts from the collection.

Within this sympathetic ambience thirty-nine artists, have attempted to pursue a common theme of the garden as earthly paradise, refuge or place of spiritual solace. These include Brian Bourke, Hughie O'Donoghue, Mick Cullen, William Crozier (Fig 6) and Gwen O'Dowd (Fig 3), all of whom enjoy the status of visiting artists in the studio. Inevitably some have chosen to interpret the original brief very liberally, others prefer a more literal approach and more work through the constraints of illustration, opting for somewhat literary and anecdotal interpretations. A good deal of the work created reflects highly individualised stylistic concerns.

Brian Bourke's etching entitled Leopold Bloom's Earthly Delights is uncharacteristically nostalgic (Fig 7). Rendered in his essential pared-down drawing style it refers to a music hall song going through Bloom's mind. The image is based on an old photograph taken in 1915 of Bourke's mother and her sisters disporting themselves on the beach at Bray. Hughie O'Donoghue's carborundum print reveals a characteristic dark brooding landscape portentous and hinting of menace. Entitled Where is your Garden? it is more evocative of an interior space, and suggests a place of sombre introspection unencumbered by extraneous colour (Fig 9). In contrast Mick Cullen's customary exuberance shines through in his submission which he calls Bongo jungle. Colourful, gestural and bordering on the chaotic the image advances and recedes, conceals and reveals at the same time (Fig 5). Dimensions are vague and movement is constant in this garden. Space is undefined. Sensuality is all.

Among the studio artists themselves one senses a more specific engagement with the terms of the overall brief. The originators of the project, Jean Bardon, Grainne Cuffe and Cliona Doyle have each demonstrated their predelictions without ambiguity. Preferring to approach the subject directly, their strengths are underpinned by masterful technique.

Jean Bardon's etching reflects her interest in the Asiatic handscrolls bordered with silk brocade which form part of the Beatty collection (Fig 10). Entitled Flora Japonica the work depicts flowers which have symbolic significance or associations with different times of the year. Plum blossom is associated with winter in Asia and Chrysanthemum refers to longevity. It is a subtle exercise in control and delicacy.

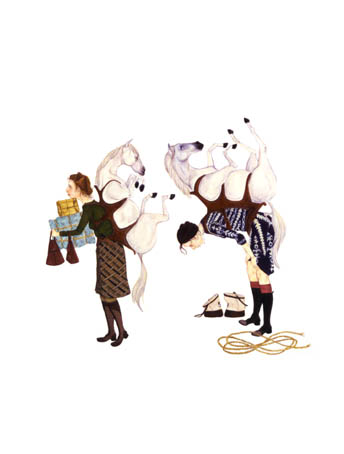

Grainne Cuffe has opted to select types of flowers which best suit her formal pictorial requirements. Her etching, which depicts Bells of Ireland, Seeds and Lillies, expresses her fascination with purely formal complexities (Fig 4). The seeds are convex tetrahedrons. The Bells which stretch across the picture plane evoke a DNA helix -- another reference to structure and the lillies exist in a space that allows for quiet appreciation of their moment of perfection.

Cliona Doyle displays comparable formal concerns in her depiction of a Black Headed Conure. She has produced an arresting image of a parrot sitting on an apple bough (Fig 1). Her composition is bold and assured, using negative space to good effect. She achieves a depth of colour and texture which is remarkable for an etching. It is one of the most tactile prints in the show.

Chinese scroll paintings provided the stimulus for Janet Pierce's aquatint. Gerwhali Raga is an evocation of a landscape remembered from a trip to the foothills of the Himalayas (Fig 8). It is a tranquil compelling study in blue melodic recollection -romantic in the true sense of the term.

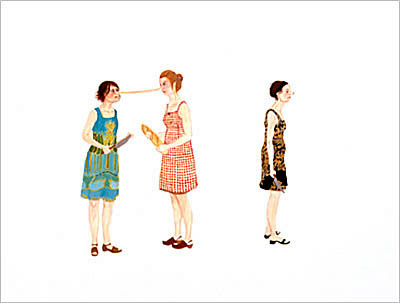

Ruth O'Donnell found her inspiration in the pages of a late medieval French book of hours. The title of the etching, Vignette suggests a pun on the practice of enclosing small manuscript imagery in a clecorative border of vines. The depiction is of a couple sharing a meal (Fig 2). The alfresco connotations are of garden tables, summer and childhood happiness.

These images best exemplify the unity within diversity which characterises the overall studio engagement with the library artefacts. They are strongly traditional in their execution and taken together they constitute a unique and substantial body of work. It is also most encouraging to note that there is no such thing as a house style within the Graphic Studio. Individuality prevails and one is left with the sense that a healthy internal dynamic exists which is further sustained and developed by external encounters.

This is plainly evidenced in the work of James McCreary. His distinctive mezzotint entitled A Visit by a Japanese Emperor is a gentle essay on whimsy. He obviously subscribes to the view that butterflies are harbingers of pleasure, joy and hope -- a welcome visitor to any garden. McCreary's confidence and formal acuity, particularly in spatial arrangement are grounded in his early experience of working at the Harry Clarke studio in the 1960s and his long time interest in Japan. Both of these great institutions have been enriched by this endeavour.

The Chester Beatty library showcases the artistic treasures of the major civilisations and religions of the world. The global collection of manuscripts, prints, miniatures, icons and early printed books is a rich national resource. By encouraging interactions such as the Gardens of Earthly Delights, thereby allowing for constant reappraisal of the concepts of museums, collections and curatorship itself, artefacts are redefined yet again, revivication is achieved and contemporary relevance is sustained. For the Graphic Studio the benefits are equally significant. Encounters with historical works reinform traditional values and techniques -- something the studio espouses. This leads to a widening of perspectives, a positive fusion of the past and the present and an increase in incremental learning for all involved. Since its establishment in 1961 the studio has provided facilities annually for etching, woodblock, lithography and carborudum printing for its members and sundry visiting artists. It is the oldest and largest fine art print studio in Ireland. Based in Dublin's docklands, it is a charitable, educational organisation and in other cultural jurisdictions it would be regarded as a national treasure. Now it faces uncertainty about its future given the pressures for redevelopment in the docklands area. Relocation may be an inevitability. Not unnaturally this causes concerns and deflects energy away from the proper concerns of the studio -- the maintenance of standards of excellence for which it has become famous. Prints from the exhibition are on sale from the Chester Beatty Library bookshop as are handmade box portfolios containing a single print from each of the thirty-nine artists.

ADDED MATERIAL

GERRY WALKER is Course Co-ordinator for Complementary Studies at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin.

1 CUONA DOYLE Black Headed Conjure 2005 etching 65 × 50cm

2 RUTH O'DONNELL Vignette Arum etching 50 × 20cm

3 GWEN O'DOWO Dracunculus carborundum 65 × 50cm

4 GRAINNE CUFFE Bells of Ireland, Seeds and Lillies 2005 etching 50 × 65cm

5 MICK CULLEN Bongo Jungle 2005 carborundum 65 × 50cm

6 WILLIAM CROZIER The Pool 2005 carborundum 37 × 44cm

7 BRIAN BOURKE Leopold Bloom's Earthly Delights 2005 etching 50 × 65cm

8 JANET PIERCE Gerwhali Raga 2005 aqua tint 31 × 25cm

9 HUGHIE O'DONOGHUE Where is your Garden 2005 carborundum 65 × 50cm

10 JEAN BARDON Flora Japonica 2005 etching and aquatint 20 × 47cm

The Garden of Earthly Delights at the Chester Beatty Library, 27 May - 2 October.