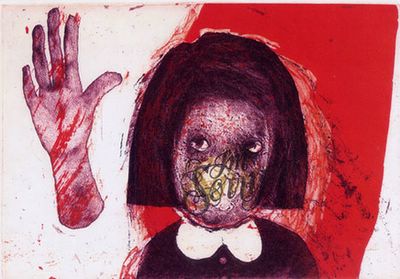

Penny Siopis

I'm Sorry, 2004. Etching, aquatint. Edition of 20. 17 3/5 x 14 4/5"

Printed by Randy Hemminghaus. Published by David Krut Fine Art

A Twenty-first Century Etching Revival

By Alexandra Anderson-Spivy

Summer 2005

What could be more old-fashioned, more traditional, or more uncool in our mad-for-digital, video-besotted early twenty-first century than etching? Today's salacious collector seems more likely to invite someone up to see his shark preserved in formaldehyde than to issue an invitation to "come up and see my etchings." Nevertheless, artists have enthusiastically embraced this process for some 500 years ever since German artist Urs Graf produced the earliest dated etching in 1513. As subsequent artists from Rembrandt and Piranesi to Whistler and Picasso have demonstrated, etching has long offered a remarkable emotional and tonal range of expression and innovation.

This versatile printmaking technique promotes, in fact requires, an intense connection between the hands-on proficiency of the artist and the delicate surfaces upon which he or she has chosen to work. It calls for painstaking plate preparation and adaptation, agility and patience. (1) It also demands fine-tuned, skilled collaborative efforts between artist and printer. (Contemporary artists often may print their own work.) In the modern world, etching has been adapted to the most arcane engineering processes; industry can routinely etch various metals, infinitely tiny computer chips, and other substances with lasers, or with chemicals or gases.

The current summer exhibition organized by International Print Center New York confirms the idea that right now there is a notable revival of interest in etching occurring among artists across the world. It's actually hardly the first time this has happened. During the latter half of the 19th century, the artists of the Barbizon School were the instigators of an earlier etching revival. Allied with the rise of interest in the sketch and in working from nature, this passionate interest in etching rapidly spread from France to England and the United States,(2) as the informality and spontaneity provided by the etching needle gained critical acceptance.

Another such revival is surely overdue. Perhaps today's artists have tired of the weightlessness of computer software, the seductions of Photoshop, the slick uniformity of the surfaces of digitally printed images. The physicality and subtleties of traditional etching processes continue to exert a powerful attraction on a surprising number of them-draftsmen and painters alike-as this exhibition demonstrates.

Diversity and experimentation are characteristics that define IPCNY's summer show. The fifty-eight works included in New Prints 2005/Summer represent work by forty-four artists and various presses across the country and from abroad. (International sources include Brazil, France, Germany, Italy and South Africa). Their work offers viewers a dazzling menu of techniques, expressive styles, and content that once again proves the relevance of etching's seductive powers.

The jury for the show examined a fascinating array of submissions. Some of the only consistent elements these works shared were a highly ambitious technical range plus an inclination to push the boundaries of the medium and a general inclination to experiment very freely with color, and scale and idiosyncratic content. It's interesting that no style or subject prevailed.

The sheer range represented by the geographical and stylistic diversity, celebrity and age of the artists who were finally selected is impressive and makes for juxtapositions on the wall that are stimulating and fresh. Veteran artists such as Polly Apfelbaum, Kiki Smith, Robert Kushner and John Walker appear here along with a panoply of artists who may be new to viewers. Apfelbaum's Love Flowers presents a cheerfully faux-naïve, intimate image of starry flowers tossed off in what could be a pattern sketched for a quilt. Kiki Smith contributes a delicate and entirely sinister rendering (Jewel) of the front feet and claws of a wolf or a very big dog against a stark white ground. Kushner in Cup of Gold prints his vibrant line drawing of a lily as direct gravure in white ink on black silk and embellishes the image with his signature squares of gold leaf. In Box Canyon, John Walker has translated the verve and scale of his abstract paintings into a waterfall of etched color and form that boils across and down across some 21 square feet (81 x 38 inches), making it the largest work in the show and one of the most powerful.

Space restrictions mean I can't discuss every artist included in the exhibition, but I will mention a few characteristic highlights. Sandow Birk's mordantly funny and cautionary image, Accidents, is from his series, Leading Causes of Death in America. Using a slyly social realist-film noir style, this artist depicts a modern woman courting danger, as she talks on her mobile while driving her car. Another sprightly image of disaster-a little cottage swept over a waterfall in black and white, appears in Dan Steeves' a hint of awe and reverence and wonder. Fernando Martí has made one of the relatively few political images in the show-his Amapolis/Poppies pairs kneeling prisoners with scarlet poppy fields. Yuji Hiratsuka's etching and aquatint images of fabulously accessorized modern Japanese women (Autumn Tints and Crops) not only update the traditions of the Japanese print with impressive skill but also combine deft social satire with ambitious technique, since Hiratsuka is both artist and printer of these works.

Several artists have used etching to create artists' books. Leslie Eliet's self-printed Sea of Dreams is a strikingly dramatic abstract narrative in accordion form. Nancy Powhida's black and white book, Cabin in the Woods has a sinister Henry Darger-like charm. Sarah Plimpton's pages for her book Doubling Back quietly harmonize poem and aquatint image.

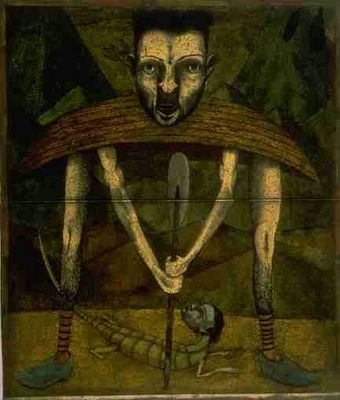

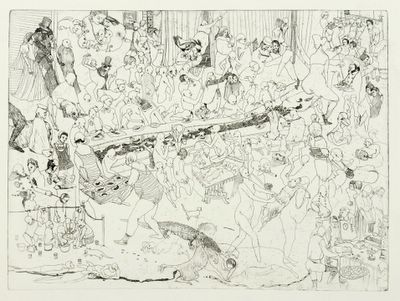

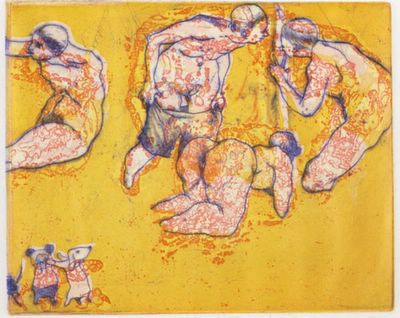

The rising young South African artist, Penny Siopis, is represented by four searing images of a child's shame and pain from her striking suite of ten etchings. Annie Heckman's She Falls in the Tank series is memorable for its beautiful draftsmanship and unusually dynamic imagery of a cat falling into water.

Several more abstract etchings are also visually compelling, technically proficient, and often clever. Justin Quinn contributes a gloss on Moby Dick that represents a "transcription" of a chapter of the book into the letter "E" in his drypoint, Moby Dick Chapter 44 or 4,349 times E. Theresa Chong's Mapping Notations and Gestures based on Bach Suite Prelude Series poetically translates sound into a mysterious black and white galaxy of points of light. Jill Parisi has contributed what may be the most unusual work in the exhibition. Her piece Stellae transforms nature into wonderful hand-colored, hand-cut etchings-evanescent paper sculptures that float in space. In short, this show offers a look at a great variety of works as contemporary artists continue their exploration of the still seductive marvels of etching.

Alexandra Anderson-Spivy is an art critic and writer who lives in New York.

New Prints 2005/Summer-Etchings Selection Committee: Desirée Alvarez, artist; Alexandra Anderson-Spivy, writer; Judy Hecker, Assistant Curator, Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, the Museum of Modern Art; Jennifer Melby, Master Printer; Harris Schrank, print collector and IPCNY Trustee; and Michael Steinberg, Director, Michael Steinberg Fine Art.